Early Office Museum

1893

1893

History of the Lead Pencil

Lead pencils, of course, contain no lead. The writing medium is graphite, a form of carbon. Writing instruments made from sticks cut from high quality natural graphite mined at Cumberland in England and wrapped in string or inserted in wooden tubes came into use around 1560. [1] The term "black lead pencil" was in use by 1565. By 1662, pencils were produced in Nuremberg, in what is now Germany, apparently by gluing sticks of graphite into cases assembled from two pieces of wood. By the early 18th century, wood-cased pencils that did not require the high quality graphite available only in England were produced in Nuremberg with cores made by mixing graphite, sulfur and various binding agents. These German pencils were inferior to English pencils, which continued to be made with sticks cut from natural graphite into the 1860s. The 1855 catalog of Waterlow & Sons, London, offered "Pure Cumberland Lead Pencils."

In 1795, French chemist Nicholas Jacques Conté received a patent for the modern process for making pencil leads by mixing powdered graphite and clay, forming sticks, and hardening them in a furnace. According to Petroski (pp. 70-71), "the brittle ceramic leads…were inserted in wooden cases of a modified design, one used by some early German pencil makers to encase their sulfur-and-graphite leads. The piece of wood into which the leads were placed has a groove about twice as deep as the thickness of the rod of lead. A slat of wood was then glued in over the lead to completely fill the groove, and the pencil was ready to be finished to the desired exterior shape."

In the U.S., wood-cased lead pencils were produced in the

Boston area by William Munroe beginning in 1812. Munroe’s cores were made from

dried graphite paste and were not hardened in a furnace. Between the early 1820s

and 1850s there were several small pencil makers near Boston, including William

Munroe, John Thoreau, Joseph Dixon, and Benjamin Ball. [2]

Munroe, of Concord, MA, exhibited lead pencils at of the

Massachusetts Charitable Mechanical Association in and around Boston in 1837,

1839, and 1841. Thoreau and then John Thoreau & Son, also of Concord,

MA, exhibited their pencils at these exhibitions in 1837 and 1844. [2a] The pencils they produced

were inferior to those made in England from natural graphite and in France and

Austria using the Conté process. [3] The photograph to

the right shows a bundle of pencils manufactured by Ball. Holden &

Cutter, Boston, MA, advertised French and English lead pencils c. 1840-60; Grigg

& Elliot, Philadelphia, PA, advertised lead pencils c. 1850-60; John W.

Clothier, Philadelphia, PA, advertised Faber's, Guttknecht, and Brookman &

Lagdon's lead pencils c. 1858. (Hagley Museum and Library)

In the U.S., wood-cased lead pencils were produced in the

Boston area by William Munroe beginning in 1812. Munroe’s cores were made from

dried graphite paste and were not hardened in a furnace. Between the early 1820s

and 1850s there were several small pencil makers near Boston, including William

Munroe, John Thoreau, Joseph Dixon, and Benjamin Ball. [2]

Munroe, of Concord, MA, exhibited lead pencils at of the

Massachusetts Charitable Mechanical Association in and around Boston in 1837,

1839, and 1841. Thoreau and then John Thoreau & Son, also of Concord,

MA, exhibited their pencils at these exhibitions in 1837 and 1844. [2a] The pencils they produced

were inferior to those made in England from natural graphite and in France and

Austria using the Conté process. [3] The photograph to

the right shows a bundle of pencils manufactured by Ball. Holden &

Cutter, Boston, MA, advertised French and English lead pencils c. 1840-60; Grigg

& Elliot, Philadelphia, PA, advertised lead pencils c. 1850-60; John W.

Clothier, Philadelphia, PA, advertised Faber's, Guttknecht, and Brookman &

Lagdon's lead pencils c. 1858. (Hagley Museum and Library)

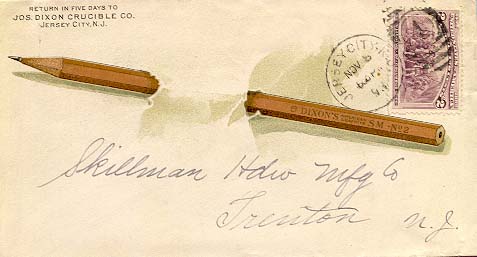

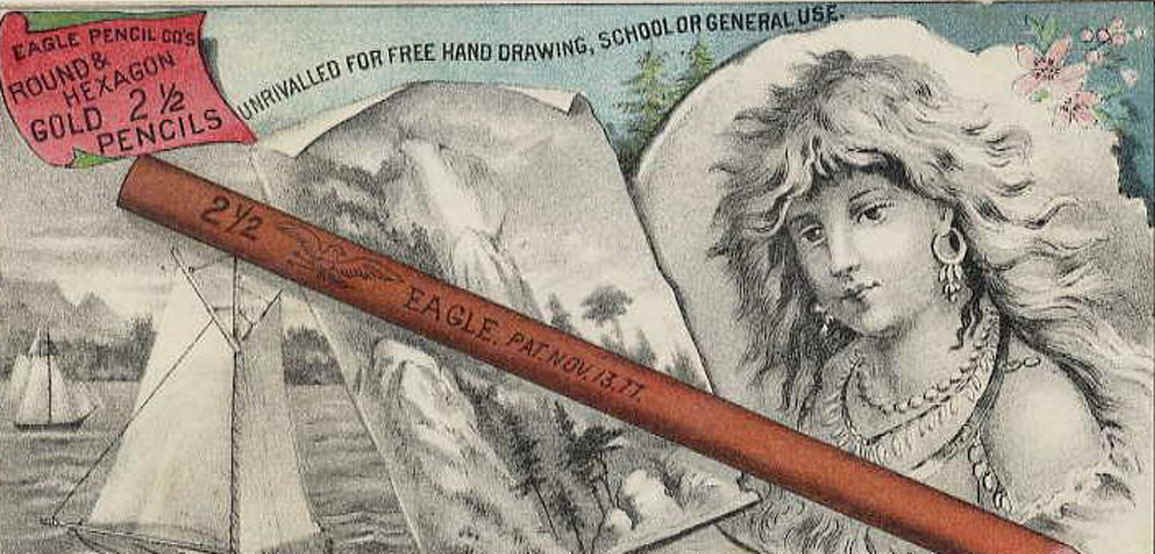

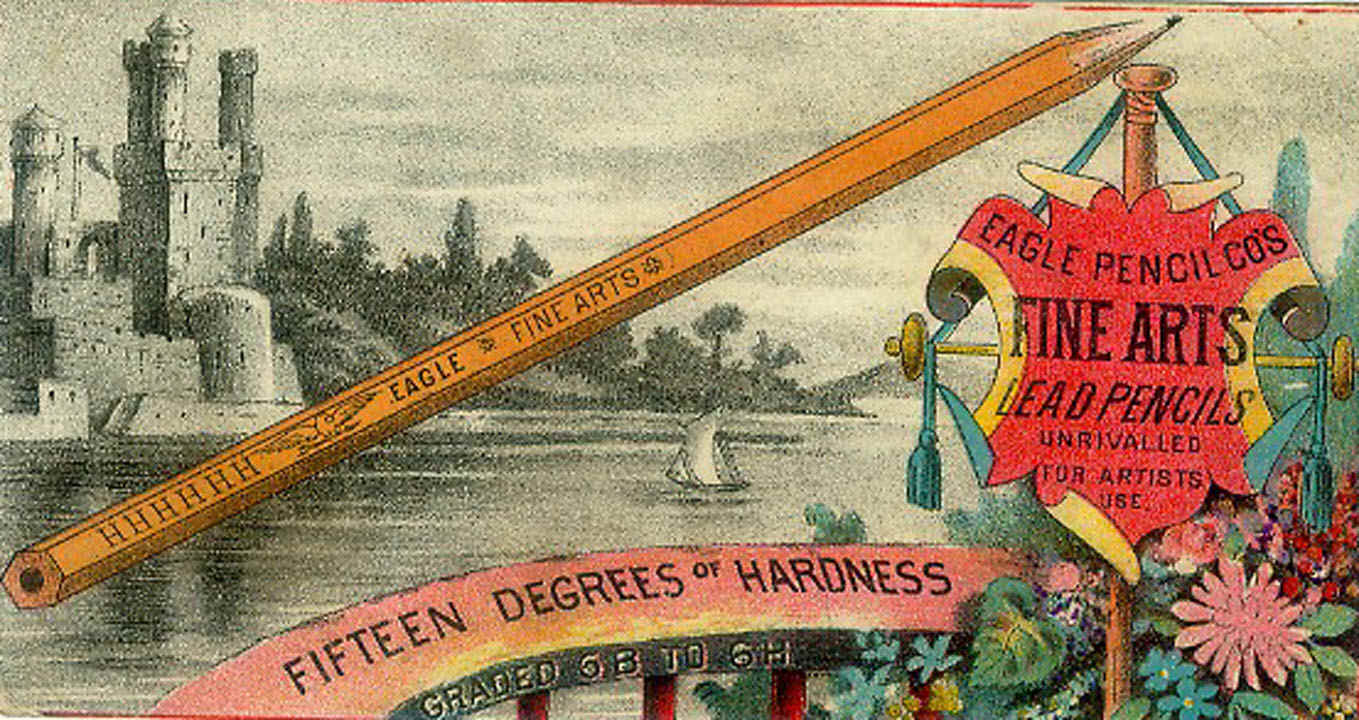

In 1847, Dixon set up a new factory just outside New York City that used graphite to manufacture crucibles for melting metals, polish for cast iron stoves, and, on a limited scale, pencils. However, most lead pencils sold in the U.S. were still imported from Europe, increasingly from Germany as the quality of German pencils improved with adoption of the Conté process. In 1861, Eberhard Faber set up a factory in New York that made pencils using leads from Germany, and in 1862 pencils made by another New York company, the Eagle Pencil Co., won an award in London. The American Lead Pencil Co. and the Joseph Dixon Crucible Co. started making lead pencils in 1865 and 1872, respectively. (Supplement to Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th ed., Vol. 4, 1889)

Mass production of lead pencils began in the U.S. after the Civil War. During 1864-67, several patents were granted for machinery for making lead pencils [4], including a Dixon wood planing machine for shaping pencils that produced 132 pencils per minute. [5] U.S. production of pencils was encouraged by the import tariff of 1865 as well as increasing demand, and the four companies that were the principal manufacturers of lead pencils throughout the latter 19th century and early 20th century—the Eagle Pencil Co., Eberhard Faber, the American Lead Pencil Co., and the Joseph Dixon Crucible Co.—all set up or expanded pencil factories in the New York/New Jersey area. [6]

American Lead Pencil Company, 1872According to Petroski (p. 169), "The demand for pencils seems to have been growing at an unprecedented rate at the time, and in the early 1870s it was estimated that over 20 million pencils were being consumed in the United States each year." In 1887, a Dixon Crucible ad stated:

In 1868 we commenced building machinery for making lead pencils, and on November 18, 1872, we shipped the first invoice of one gross [of pencils] to Voorhees Bros., Morristown, N. J. Now our sales are beyond what our wildest expectations were then. We began in a building 25 x 25, with four or five hands, and now use one hundred thousand square feet of floor space and employ four hundred hands. In the beginning we had only three or four kinds [of pencils] for business and school uses; now we make hundreds of different kinds for business offices, schools, drawing classes, artists, architects, and mechanical draughtsmen, besides making a large variety of pen-holders, point protectors, slate pencils, artist’s cases, special leads, assortment boxes, erasive rubbers, etc., etc. [7]

In

1878, Charles J. Cohen, Philadelphia, PA, advertised Dixon American Graphite

lead pencils. By 1891, Dixon Crucible was issuing stock certificates. In 1892, Dixon Crucible alone manufactured more than 30

million pencils. [8] Petroski (p. 182) reports that "One observer, writing in

1894, noted that in twenty years the cost of pencils had been reduced by 50

percent, at least in part because of the invention of machinery such as that

used by Dixon.". Petroski (p. 205) reports an estimate that in 1912 U.S. and

world production of pencils were 750 million and two billion pencils,

respectively.

Before a market for mechanical pencil sharpeners could be

developed, it was necessary not only that a substantial number of pencils were is

use but also that these pencils could be sharpened by a machine. The easiest

pencil to sharpen with a machine is one with a round or hexagonal wood case

that has a round lead that is centered in the case.

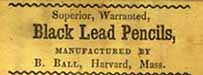

The pencils made by Benjamin

Ball in the mid-19th century had square leads that were typically off-center and

the wood cases were somewhat out-of-round, as the photo to the right reveals.

Before a market for mechanical pencil sharpeners could be

developed, it was necessary not only that a substantial number of pencils were is

use but also that these pencils could be sharpened by a machine. The easiest

pencil to sharpen with a machine is one with a round or hexagonal wood case

that has a round lead that is centered in the case.

The pencils made by Benjamin

Ball in the mid-19th century had square leads that were typically off-center and

the wood cases were somewhat out-of-round, as the photo to the right reveals.

Round lead was used in mechanical pencils

by the early 19th

century. The illustration to the right shows mechanical pencils from an 1883

office supply catalog.

Round lead was used in mechanical pencils

by the early 19th

century. The illustration to the right shows mechanical pencils from an 1883

office supply catalog.

However, square lead continued to be used in most wood-cased pencils until the mid-1870s. (Petroski, p. 184). Wielandy (p. 67) states that "All the black lead pencils exhibited at the Centennial in Philadelphia in 1876 contained square leads, and it is said that Joseph Dixon Crucible Company was among the first manufacturers of pencils to use round leads, making the change shortly after the Centennial year." [9] In its 1881 catalog, Robert Clarke & Co., a stationer, advertised Dixon American Graphite, American Lead Pencil Co., and imported A. W. Faber pencils, all with a choice of round and hexagonal cross-sections for the wood cases. The Dixon pencils illustrated in the catalog had square leads while the Faber pencils had round leads.

The explanation for use of square lead in wood pencils is that when square lead was used, it was necessary to cut a groove in only one of the two pieces of wood used to make the case. In order to use round lead, it was necessary to cut matching grooves in the two pieces of wood. Petroski reports that limitations of woodworking machinery may have prevented round lead from being widely used in wood-cased pencils until the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Petroski states that by the late 1870s U.S. pencil makers had machines with the precision and speed to mass produce wood-cased pencils with round leads. (Petroski, pp. 186, 251) In other respects as well, by the late 1870s the pencils made by the four large U.S. companies, which engaged in research and development to improve their pencils, were of substantially higher quality than the pencils made before the Civil War by the small Boston area companies. (Petroski, pp. 336-37)

Thus, by 1880 there was a potential market for mechanical

pencil sharpeners. Click here to read about

the development of early mechanical pencil sharpeners.

Trade cards advertising Eagle Pencil Co. products

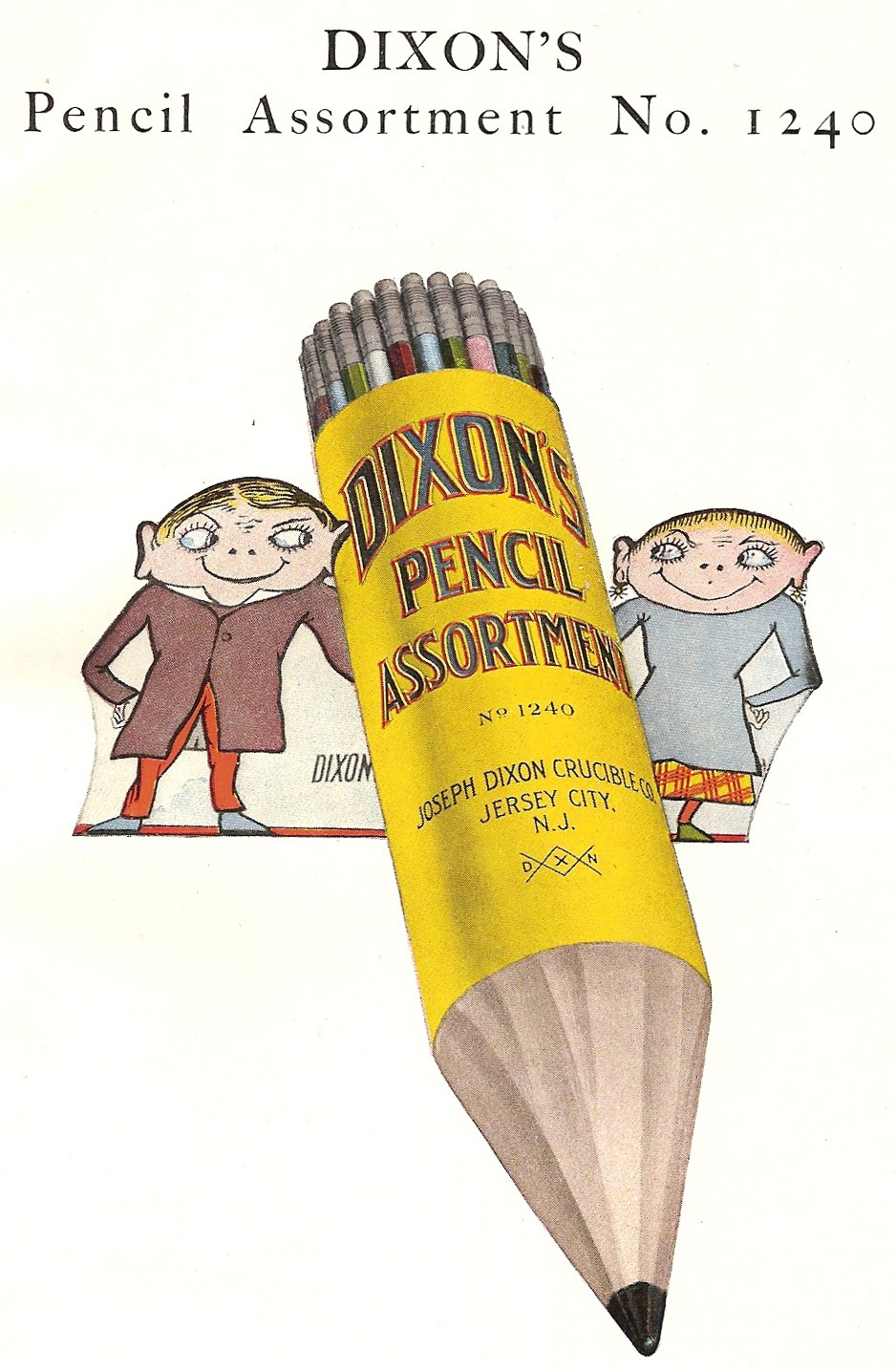

1912 advertisement for Dixon's lead pencils. The large pencil appears to have

been whittled.

Courtesy of the Museum of Business

History & Technology

Rubber Erasers

"India rubber," evidently intended for use as a pencil eraser, was advertised by William H. Maurice, a Philadelphia, PA, stationer, in 1847. Erasers were attached to the ends of pencils by 1853, when Charles Goodyear wrote: "Pencil-Heads. These are made of the artist's India rubber...; they are set into metal sockets...or are formed into rings or heads which are intended to slip over the ends of a wooden pencil..." (Charles Goodyear, The Applications and Uses of Vulcanized Gum-Elastic, Vol. II, New Haven, 1853, p. 39) "Rubber erasers" and "Rubber pencil-tips" are listed among the purchases for members of the 1869 Illinois Constitutional Convention. (Debates & Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention of the State of Illinois, Sept. 13, 1869) "Rubber erasers" were advertised by Charles J. Cohen, a Philadelphia, PA, stationer, in 1878. It was reported in 1880 that "The new style of rubber eraser inserted in the head of the pencil has proven very popular." (The American Bookseller, Jan. 1880, p. 16) Both a "Stationers' Rubber" and a rubber "Crystal Eraser" were advertised by The American News Co., New York, NY, in 1883, and the same company advertised "Rubber pencil and ink erasers" in 1884. (Hagley Museum and Library)

Slate Pencils

White

slate pencils made by John Cain & Co., Rutland, VT, were exhibited in 1844

at the fourth exhibition of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association in

Boston, MA. From that time, if not earlier, through the early 20th

century, pencils cut from solid pieces of softer grades of

slate or soap-stone were used by schoolchildren to write on tablets cut from

harder grades of slate. Apparently, artificial slate pencils were also made; for

example, Patent No. 316,374 award to Samuel Kraus on April 21, 1895, describes a

method of making slate pencils using ground talc or soapstone mixed with ground

potter's clay. Slate pencils were available with the slate core

unwrapped, wrapped in paper, and encased in wood like a lead pencil. Holden

& Cutter, Boston, MA, advertised slate pencils c. 1840-60; Grigg &

Elliot, Philadelphia, PA, advertised slate pencils c. 1850-60; Charles J. Cohen,

Philadelphia, PA, advertised slate pencils, including wood-cased ones, in 1878.

(Hagley Museum and Library) We have

seen advertisements for slate pencils dating as late as 1914. According to Wielandy (p.

91), wood-cased slate pencils were still sold in the early 1930s.

Paper-wrapped slate pencils

Britannia Box of Slate Pencils, made in Germany

Eagle Pencil Co. wood cased slate pencils with fiber erasers

Some mechanical sharpeners were designed exclusively for slate pencils, but a number of 19th century mechanical sharpeners were marketed for use in sharpening both lead and slate pencils.

Pencil

Vending Machines E.W. Peck Co, New York, NY, advertised a pencil vending machine in the July 1910 issue of Book-Keeper magazine. That ad stated "The machine is new--an absolute innovation in vending devices, as pencils have never been sold through slot machines before." The same ad claimed that a thousand of these machines were already installed in New York. Other pencil vending machines were marketed by Osborne Specialty Co., Parker Pencil Services, Clawson Machine Co., Charles Weeks Co., Miller Vending Machine Co., and Bally Manufacturing Co. In 1923 Weeks offered a pencil vending machine that printed up to 16 letters (for example, OFFICE MUSEUM) on the pencils as they were dispensed. In 1928 and 1936, Miller advertised a pencil dispenser with a pencil sharpener on top. In 1938, Bally advertised its 56-inch tall electric Rainbow Pencil Vendor. Vintage ads for these machines can be viewed by searching the historical magazine archive available online at http://arcade-museum.com.

Peck Pencil Slot Machine 1911 ad

Osborne Pencil Vending Machine

Clawson Pencil Vending Machines ad

Miller Pencil Dispensing Machine with Pencil Sharpener 1928-36

Notes:

[1] This historical sketch is based on numerous articles on the subject in the late 19th century and early 20th century trade press; Henry Petroski, The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance, Knopf, NY, 1989, 1998; Leonard C. Bruno, Science and Technology Firsts, Gale, 1996; and histories available on the web sites of Incense Cedar Institute (http://www.pencils.com); Dixon Ticonderoga (http://www.prang.com); and Sanford Berol (http://www.berol.com.uk). [Back to text][2]

The Ball Pen and Paper Co., Harvard, Mass., produced

pencils from 1830 until shortly before the Civil War. Based on research gathered

at the Harvard Mass. Historical Society, Rich Karlowsky supplied the following

information: "In 1830, Mr. [Benjamin] Ball set up shop in the Mill District

of Harvard, Mass…. On one floor he manufactured paper and on the other…pencils….

John Thoreau and Benjamin Ball were producing pencils at the same time. Thoreau

pencils were considered high quality because of the darker lead. Ball also

produced a pencil, but it did not write as well as the Thoreau." Mr.

Karlowsky acquired bundles of Ball pencils that were found in the attic of an old

schoolhouse. Each bundle consists of a dozen cedar pencils with square leads,

tied together with thread and with a paper label that reads "Superior

Warranted Black Lead Pencils Manufactured by B. Ball, Harvard, Mass." For a picture of a similar bundle of Thoreau pencils, see

Petroski, p. 314. The pencils, which are shorter and thinner than the standard

pencil produced today, are only approximately round, and no two have the same

cross-section. While the leads in some of the pencils are approximately

centered, some of the leads are well off center. [Back

to text]

[2a] First through Fourth Exhibition of the Massachusetts

Charitable Mechanic Association, Boston, 1837, 1839, 1841, 1844.

[3] A mechanical (or "propelling") pencil was patented by Sampson Mordan and John Isaac Hawkins in Britain in 1822. For a history and superb pictures of early mechanical pencils, see Deborah Crosby, Victorian Pencils: Tools to Jewels, Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, PA, 1998. Crosby (1998, p. 62) states that "Huge numbers of patents were issued for a variety of advancements or improvements in propelling pencils during the nineteenth century (between 1820 and 1873, more than 160 patents were listed pertaining to mechanical pencils)." In the U.S., patents for mechanical pencils predate the earliest patents for wood-cased lead pencils or pencil sharpeners. [Back to text]

[4] U.S. Patent Nos. 43,267; 45,679; 54,511 (Dixon, 1866); 62,829. [Back to text]

[5] Petroski, p. 169; "Dixon Ticonderoga Company," International Directory of Company Histories, St. James Press, Vol. 12, 1996, p. 115. [Back to text]

[6] According to an 1891 account, "The manufacture of pencils was until about 1863 confined almost exclusively to Germany…; but with the [U.S.] tariff of 1865 the business was started here, and new methods were introduced, automatic machinery being largely adopted, and a reduction in the cost of production followed until lower prices than had ever been known were reached. In 1878 a combination was made among the makers, and it continued until 1889, realizing a large profit to the four manufacturers interested. The agreement was broken up in the latter year, and the market broke on all except the finer grades, which sold on brands, and today no one can complain of the price of pencils or the quality, for the commercial grades are superior to the finest produced thirty years ago." Letter to the Editor, The American Stationer, April 16, 1891, p. 825. [Back to text]

[7] The Stationer and Printer, Jan. 1, 1887, p. 1742. [Back to text][8] Walter Day, "Dixon American Graphite Pencils," Business, April 1892, p. ix. [Back to text]

[9] Paul J. Wielandy, The Romance of an Industry: A Retrospective Review of the Book and Stationery Business, Blackwell, Wielandy, St. Louis, 1933. Wielandy was in the wholesale stationery business by 1884. [Back to text]