|

| Antique Communications Equipment |

Antique

Communications Equipment

This exhibit traces the development of technologies used by offices for two purposes, communications within an office or office building, and communications between an office building and the outside world. It is reasonable to assume that, before our story begins in the mid-1800s, office boys and messengers were used for both types of communication. The technologies discussed here were revolutionary for their times, just as CMMS software is today. CMMS is used in a variety of facilities for equipment maintenance management.

|

Communications Within a Company In 1884, it was reported that at the Boston Herald, "electric call-bells, speaking tubes, and pneumatic tubes furnish means of communication with all the departments." (The Bay State Monthly, Oct. 1884, p. 32). This brief statement accurately describes the state of interoffice communications technology at that time. |

. |

| Speaking Tubes

"Two persons standing at each end of a simple tin pipe, 1 inch in

diameter, 50 to 100 feet or more long, with several elbows in it, and

carried through a half a dozen rooms, can still converse quite readily in

a low voice." (Manufacturer and Builder, Mar. 1872, p. 67) During the second half of the nineteenth century, speaking tubes were

commonly installed in the walls of mansions, office buildings, ships, and

other structures to enable people in different rooms to speak with each

other. In some cases, only a mouth-piece was visible, while in other cases

a piece of flexible tube extended into the room. Early systems contained

whistles, so that a person could alert someone in another room that they

were wanted on the speaking tube. (Scientific American, May 29,

1852, p. 292) Later systems incorporated electric call bells that could be

used for the same purpose. In 1860, offices at the New York telegraph

building were connected by speaking tubes. (Scientific American,

June 8, 1860, p. 372) In 1876, the new Post Office building in New York

City had eight miles of speaking tubes. (Manufacturer and Builder,

Dec. 1876, p. 272) The catalog of the Fourteenth Exhibition of

the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanical Association, Boston, Mass,

1881, p. 195, reports that Seth W. Fuller of Boston exhibited speaking

tubes and annunciators. We have found three photographs of offices with speaking tubes, all of which, are shown to the right. In the middle photograph, four speaking tubes are visible at the front left. In the bottom photograph, a button that operated an electric call bell is visible below the mouth-piece of each speaking tube on the pillar on the right side of the photo. |

|

| Call Bells and Annunciators

Around 1850, some large homes had mechanical call bell systems that

connected various room with the kitchen so that servants could be

summoned. We do not know whether such systems were used in offices. |

|

| Pneumatic Tubes

In 1881, pneumatic tubes carried cash and receipts between sales counters and the central cashier at the John Wanamaker department store in Philadelphia (Manufacturer and Builder, Jan. 1881, p. 20) and documents among offices in the London Times building (Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Nov. 1881, p. 843). In 1896, pneumatic tubes were used at the New York Postal Telegraph to transport written telegrams between the main telegraph office and the room where the telegraph operators worked. (Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Oct. 1896, p. 734) During 1898-1906, Lamson Consolidated Store Service Co. advertised a foot power pneumatic tube system for transmission of papers between offices within a building. Lamson's 1898 brochure included photographs of one of its pneumatic tube systems at the Boston Journal. A 1906 Lamson ad stated: "Pressure of the foot gives quick service between floors or departments, or between office and shipping room." In 1906, a considerably larger Lamson pneumatic tube system was operating in the Chicago post office building, "connecting all the offices of the postal department as well as the other federal officials who are located there, with the central receiving and sending station on the main floor of the post office. This local system comprises 16 lines of four-inch brass tubing, requiring more than two miles of tubing altogether. Cartridges fly through these tubes at the rate of 30 miles an hour. This system is used for intercommunication between offices and for delivery to the post office." (The Business Man's Magazine, 1906) Automatic messenger systems, such as Lamson Mechanical Messengers, were used in offices to carry documents and other light articles. (Lawrence R. Dicksee, Office Machinery and Appliances, London, 1916-18, p. 10)

According to a 1937 text, "Pneumatic tube conveyors are used quite extensively in modern office buildings. Large elliptical pneumatic tubes are used for the distribution of mail, while 1 1/4 inch 'baby tubes' may be used to transport small papers. Belt conveyors are often used to carry papers, while basket conveyors and dumb-waiters quickly carry more bulky material up and down through the floors of the building." (John S. MacDonald, Office Management, 1937, pp. 85-86) Click

on this link to the Wisconsin

Historical Society, Wisconsin Historical Image, No. 13866, for a

photograph of the pneumatic tube system in the State Capitol Annex,

Madison, WI, 1942. |

Image W coming |

| Telephone Alexander Graham Bell demonstrated a telephone at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. The first telephones were point-to-point systems, and Yates reports that "early installations of point-to-point telephones often linked the office and factory of a single firm....Beginning in the 1890s, private branch exchanges were widely adopted to link many locations within large facilities." (JoAnne Yates, Control through Communication, 1989, p. 21) More information on early telephones is provided below. |

|

| Acoustic Telephone

Holcolm's Acoustic Telephone, 1879 ad |

|

Kellogg Intercom Phone, Stromberg-Carlson Mfg. Co., Rochester, NY, patented 1894 Intercommunicating Telephone System (Intercom) The Kellogg intercom phone pictured above was patented in 1894. The Simplex Interior Telephone Co. offered intercommunicating equipment in 1896, and offered the model pictured to the right in 1900. The Electric Utilities Co. advertised the Metaphone intercommunicating system in 1905. "How would you like to simply put out your hand, unhook a small device, and be in instant communication with [someone in your company]? The Metaphone enables you to do this. It is a transmitter and receiver mounted on opposite ends of a small metal handle. It requires only the current necessary to ring an electric bell." The devices could be connected in a network, so that any two could communicate without a central switchboard, or radially, in which case only the central station could communicate with the others. Intercommunicating

telephone systems similar to the DeVeau and Stromberg-Carlson pictured

below and the Lennox pictured to the right were

advertised in 1905 and the following years by several additional companies, including

Electric Goods Mfg. Co. (1908-10) and Western Electric Co. (1908-14). One ad stated: "No operator is required. Simply pressing a

button calls the desired person and you talk." A 1912

advertisement for the Dictograph-Turner telephone system stated "no

switchboard, no operator, no waiting." With that system, a user

had a choice between listening with a handset or a loudspeaker in the

desktop console.

A 1937 text states: "The Dictograph is frequently used, particularly in large organizations where a supplementary inter-communicating system which provides direct connection between a relatively small number of individuals, often officers and chief executives, is desired. The receiver and mouthpiece are similar in appearance to the hand telephone. Connection is made by the person calling simply by depressing a small key, which is marked to indicate a particular individual." (John S. MacDonald, Office Management, 1937, pp. 87-88, showing a unit similar to that in the lowest photograph to the right) |

|

| Communications With Parties Outside the Company | |

| Postal Service Click here to go to the Early Office Museum's Mail Room Equipment Exhibit |

. |

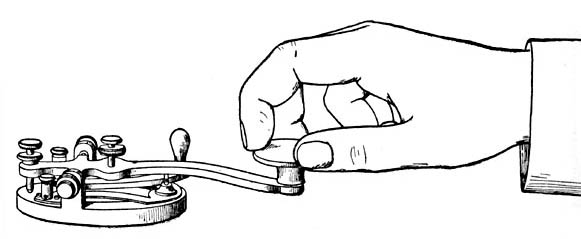

| Telegraph

The transmitting device in a Morse telegraph system was a key, which the

operator used to close and open an electric circuit following a code

consisting of dots and dashes. The receiving device included a

pencil that wrote the dots and dashes on paper tape, and then a sounder,

which converted electric impulses into noises that were transcribed by

telegraph workers. On long lines, a relay with a local battery was used to

move the lever of the sounder with greater force, making the sounds more

audible. In a Callard battery, zinc was located above copper in jars

filled with a solution of blue vitrol in water and connected in series.

According to an account by Robert Sobel: "In 1832 Samuel F. B. Morse developed the first practical [electric wireline] telegraph. He hoped to interest businessmen in his scheme of linking large cities by telegraph, but for ten years he attracted little attention. In 1844 he built the first land telegraph, a line which ran between Baltimore and Washington. Business finally awoke to the potential of such devices, and the Magnetic Telegraph Company was formed in 1844 to operate a line from New York to Philadelphia. [W]ithin two years Magnetic Telegraph showed a profit. By the mid-1850s there were over fifty telegraph companies in operation; in 1856 Western Union was formed, and began absorbing smaller firms." (The Big Board, 1965, pp. 52-53) Yates (pp. 23-24) reports that in 1851 "The New York and Erie Railroad was the first line to initiate regular telegraphic control of train movement, called dispatching....Dispatching was a specialized railroad function, but the telegraph could also be used for more generic managerial functions. Once again, the Erie Railroad led the way, this time under the general superintendency of Daniel McCallum. As his 1856 Superintendent's Report explained, hourly telegraphic reports were a key element of the system he designed to control and evaluate performance." Other railroads did not routinely use the telegraph for dispatching or managerial control until the 1860s. Yates (pp. 118-19) reports that "After 1863, the [Illinois Central] Railroad regularly used telegraphic dispatching to handle schedule disruptions" and "the telegraph was also used to speed routine reporting along the road and, to a lesser extent, to New York." In 1855, the Du Pont black powder manufacturing company installed a

private telegraph line connecting its Brandywine offices to the telegraph

office in Wilmington, DE. (Yates, p. 207) During the administration

of President Hayes (1877-1881), according to a recent report the

"White House ignored the newly invented typewriter, and although it

boasted a telephone, there were so few elsewhere that it was seldom

used. The center of communications in the White House was its busy

telegraph office." (Ari Hoogenboom, The Presidency of

Rutherford B. Hayes, 1988, p. 58) After railroads, the leading

meat-packing companies, Swift and Armour, were early users of the

telegraph. Beginning in the 1880s, these companies slaughtered cattle in

the midwest and shipped beef east to markets in refrigerated railroad cars.

(Yates, pp. 24-25) |

Key, 1883 Sounder, 1883 Sounder & Key, 1883  Relay, 1883  Callard Battery, 1883  Sounder, 1900  Key, Germany  Sounder & Camelback Key, L. G. Tillotson & Co., New York |

|

To the right is an image

of the

Burlingame Telegraphing Typewriter (1908) with a standard typewriter

mounted on top. An operator typed a message on the standard typewriter,

producing a typed record of the message. At the same time, as each key was

depressed, the Burlingame device sent electrical impulses to a remote receiving

Burlingame device equipped with a typewriter, which typed the same

message. The electrical impulses could be sent over wires or without

wires. Company stock certificates are decorated with an illustration of

ship-to-shore communication. During 1908-09, the Burlingame Telegraphing

Typewriter Co. produced

demonstration machines and set up a factory. In an effort to raise equity

capital, employees, including George C. Clark, "demonstrated the Burlingame telegraph on road trips for about

a year in 1908 and 1909. No one seems to know for certain what happened to

the company, but I suspect it was lack of money to continue. The sales

crews did not sell anywhere near the amount of stock [certificates] that they had planned

to." (Information courtesy of Clark Family Research and George C.

Clark: Burlingame Telegraphing Typewriter Company, 1908-1909, A

description of life on the road demonstrating the Burlingame Telegraphing

Typewriter, Clark Family Research (333 Avenue B, Lakeport, CA 95453),

2003.) According to Adler

(1997, p. 89), the machine did not go into commercial production. Teletype |

Typewriter Telegraph, Scientific American, Jan. 19, 1895  Yetman Transmitting Typewriter Courtesy of the Museum of Business History and Technology  Stearns Visible Typewriter mounted on a Burlingame Telegraphing Typewriter, 1908-09 American Keyboard Transmitter, American Transmitter & Mfg. Co. This transmitter, which was advertised in 1910, sent Morse code.

|

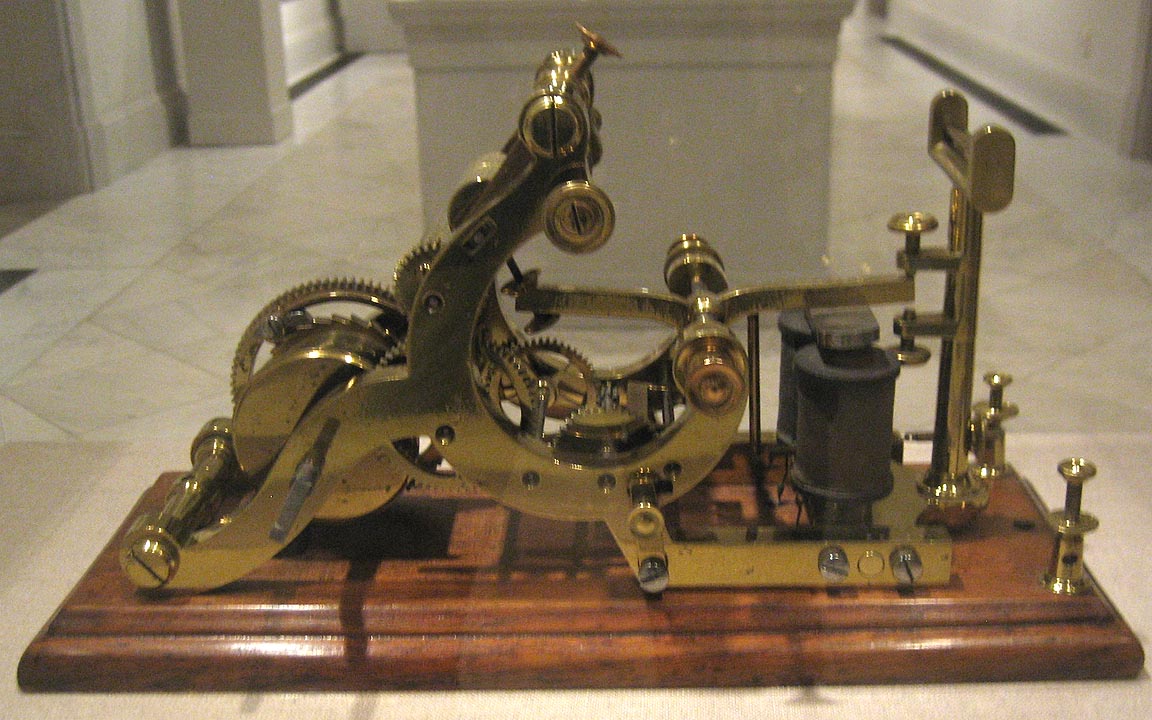

| Tickers

A ticker system uses telegraph technology to distribute stock and commodity quotations as well as related financial news to subscribers, including particularly brokerage houses. The first ticker system was patented by E. A. Calahan in 1867. The Gold and Stock Telegraph Co. began using Calahan tickers to report New York Stock Exchange transactions to brokerage houses on Nov. 15, 1867. According to Robert Sobel, "The tickers sent out prices from the floors of both the [New York Stock] Exchange and the Open Board to brokerages for a fee of $6.00 a week. The machine caught on immediately....Soon every major house had its crude battery-operated machine." (The Big Board, 1965, pp. 86-87.) During 1869-1873, Thomas A. Edison made a number of improvements to stock ticker technology for the Gold and Stock Telegraph Co. and for the Western Union Telegraph Co. Edison's Universal stock printer became the industry standard. A ticker system consisted of transmitters and tickers.

As of 1883, quotations were sent using a According to an 1883 report,

"At present the Gold and Stock Telegraph Company has about 1,000

instruments [tickers] in operation in the various brokers' and bankers'

offices, the leading hotels and other places of resort by speculators, all

of which furnish only the sales and quotations of the Stock [New York]

Exchange. The Commercial Company has several hundred tickers in

operation. It has been in business only a short time and the number

is rapidly increasing. The Gold and Stock Company also operates

about 300 instruments, which give quotations of cotton and petroleum and

of mining stocks, and about 300 more which furnish financial news,

miscellaneous quotations and other matters of interest on Wall

Street." (G. L. Howe & O. M. Powers, The Secrets of

Success in Business, 1883) |

|

| Telephone

Telephone exchanges were invented in 1877-78. The world's first commercial telephone system, the Connecticut District

Telephone Co., opened in Jan. 1878. Its Nov. 1878 directory lists

391 subscribers, who paid $22 a year each. Users needed to transfer

the telephone between their mouths and ears, and "were limited to

three minutes a call and no more than two calls an hour without permission

from the central office." The system was a single party line,

that is, only one call could be made at a time, and any subscriber who

picked up a phone could listen in. (New York Times, June 10,

2008, p. D3, discussing a forthcoming Christie's auction at which a copy

of the telephone directory was to be sold.)

|

|

| Telautograph -- A system to transmit

handwriting by wire -- also used within companies Telegraphs using Morse code or typewriters could not transmit handwriting, including signatures, or drawings. Telautographs were designed to fill that gap. After attempts by a number of inventors, in 1887-88 Elisha Gray invented what became the first commercially successful telautograph. The Gray National Telautograph Co. was founded in 1888, and its products based on Gray's patent were introduced to the market in 1893. The first commercial units were installed at the American Bank Note Co. The telautograph was refined during 1893 and 1900, and the improvement designed in 1900 was marketed for several decades. According to a 1893 description of the Gray Telautograph, "In

transmitting a message, drawing, sketch, or whatever may be desired, the

sender takes an ordinary lead pencil and writes or draws his message with

it on a sheet of paper, and simultaneously another pencil at the receiving

end of the line reproduces every movement of the sender's pencil on a

similar sheet of paper. The receiving pencil is actuated entirely by

automatic electric mechanism, and is not touched by the human hand. The

result is a fac-simile in every detail of the letters of the message or

lines of the drawing sent from the transmitting station." (Manufacturer

and Builder, April 1893, p. 76. This article includes

illustrations of the first three models of the telautograph.)

Messages were transmitted over two-wire circuits such as telegraph wires.

Apparently early telautographs did not work well for transmission over

long distances and as a result were used primarily within metropolitan

areas. The Gray National Telautograph Co. was still operating in 1905. A 1905 article states that "the telautograph did not come into extensive general use until quite recently. Business people did not begin to take real hold of it till the middle of 1903." The article continues: "the leading banks and trust companies of New York, Boston and Philadelphia have adopted it. In some large banks it is used as an intercommunicating system connecting the various departments. The advantage of the telautograph system in banks lies largely in the value of the records kept of communications. The big insurance companies have also adopted the telautograph. Up to the present these have found it most useful for communications between their policy loan department and the index room where the records of policies are kept on file. Several Wall Street firms have installed the machine in the place and stead of messenger boys for service between their offices and those of the telegraph and cable companies. (H. V. Ross, "Commercial Use of the Telautograph," The Business Man's Magazine and The Book-Keeper, May 1905. This article includes an illustration of a 1905 model telautograph.) According to another report in 1905, an "interesting instrument that one finds in an up-to-date electrically equipped office is the telautograph, which automatically reproduces handwriting in facsimile at a point more or less distant. Where it is necessary to give exact information to a number of persons simultaneously and have the same a matter of record, this instrument is very convenient. For example, a train-dispatcher can announce the movements of trains to a number of officials stationed at different points by simply writing a single message. The device is also employed by newspapers and other concerns for writing bulletins. When used in a bank the cashier or teller may inquire from the bookkeeper as to the amount of balance or other particulars of a customer's account, the message and the answer being noiselessly received." (Harper's Weekly, July 1, 1905. This article includes a photograph of a 1905 model Telautograph.) A 1937 text states: "The Telautograph is used rather extensively for transmitting written messages between offices. Messages are written in longhand with a special pen. The writing is then reproduced in exactly the same way, usually on a roll of paper, at the receiving station." (John S. MacDonald, Office Management, 1937, p. 86) In the 1940s, Telautograph marketed an improved model under the Telescriber name. |

|

| Telegraphones -- Telephone

recording machines

According to an 1889 report, Malone Wheless invented a telegraphone that recorded telephone messages, but we have found no evidence that this device was manufactured commercially. (The Phonographic World, Oct. 1889, p. 44) In 1898, Valdemar Poulsen, a Dane, obtained the first patent for electromagnetic sound recording. In 1900, he demonstrated a telegraphone based on his patent. The U.S. rights were purchased by the American Telegraphone Co. in 1903. This company was still in business in 1923. The telegraphone could record sound from live dictation or from a telephone line and could play back the recording through a speaker or over a telephone line. As a result, it could be used (a) to record dictation to be played back to a stenographer on the same machine or to be sent to a stenographer over a telephone line; (b) to record a two-way telephone conversation; (c) to record telephone messages when no one was available to answer the phone; and (d) to send a pre-recorded message over the telephone to multiple receipt points. There were two types of telegraphone as of 1905. One type recorded magnetically on a steel wire and the other magnetically on a steel disc. The wire telegraphone "contains about two miles of fine (.01 inch in diameter) steel wire, which is sufficient for about a half-hour's conversation, but at any time a message or all messages may be effectively effaced at will, when the apparatus is ready for new records." It has recently been reported that "the most successful of the early office dictation Telegraphones was the Model C [produced in 1911], with horizontally-mounted spools for better wire control" (in contrast to the earlier 1905 model top right, which had vertically-mounted spools). (Pavek Museum of Broadcasting) In the case of a disk telegraphone, "the record is made on a thin metal disc. The record is quite permanent, and can be removed only by a strong magnet, which, however, will efface it altogether." The disc telegraphone pictured to the right had a recording capacity of 2 minutes per disc. For a 1905 photograph of a different disc telegraphone model that used a smaller disc, see Harper's Weekly, July 1, 1905. According to an article published in 1906, "the telegraphone is not in use as yet among the business public." (E.F. Stearns, "A Spool of Wire Speaks," Technical World Magazine, Dec. 1906, pp. 409-12.) |

|

| Facsimile Machines During the 19th century, at least three systems were invented for transmitting copies of messages, drawings, and photographs. These systems used a transmitter with a stylus that passed over the message or image numerous times, and activated a remote receiver with another stylus that drew a facsimile. The first of these systems was introduced by Alexander Bain, a Scot, in 1842. This system was not a commercial success. Another system was introduced by Frederick Bakewell in 1848. And another system was introduced by N. S. Amstutz c. 1892. The top two images to the right show Amstutz's Electro-Artograph. According to the description, when a stylus in the transmitter went over a specially prepared photographic image, a stylus in the receiver created a line engraving that was ready for press printing. For further information on the Anstutz system and an example of an image created by the receiver, see "The Photo-Electro-Artograph," American Journal of Photography, Jan. 1892, pp. 34-35, and N.S. Amstutz, "Acrograph Engraving Machine," The Photographic Times, 1899, pp. 446-47. Arthur Korn introduced the first practical photoelectric technology for scanning and transmitting photographs in 1902. During the mid-1920s, Western Union and other companies introduced photograph transmission services, mainly for use by newspapers, and in 1930 Western Union introduced facsimile message service. The bottom photo to the right shows Warren Jones in New York watching the signature of his client Ralph Beaver Strassburger, a wealthy businessman, being transmitted by wire from London. The photo is undated, but the internet has many references to Mr. Strassburger dating from the 1930s. In 1966, Xerox introduced the desktop Xerox Magnafax Telecopier. Office use of facsimile machines expanded during the 1970s and, particularly, the 1980s. The number of fax machines in the US increased from 300,000 in 1982 to 1,500,000 in 1988 (Xerox Crop., Facsimile: A Quarter-Century of Innovation, 1989).. During that period, office workers typed documents, or printed documents created on word processors and computers, and then scanned and transmitted the documents using fax machines. By the end of the 1990s, use of fax machines declined because documents were increasingly transmitted directly between computers over the internet. |

|