|

| Antique Typewriters |

The Earliest Writing Machines

A

writing machine was patented in England in 1714, a music typewriter was invented

c. 1747, and a machine that enabled a blind person to write letters to a sighted

person was made in 1808. Between 1829 and 1870 inventors in Europe and the

US patented numerous

writing machines with a wide range of designs. One of these early machines,

Charles Thurber's 1843-45 Patent Printer, is

pictured to the right and immediately below.

A

writing machine was patented in England in 1714, a music typewriter was invented

c. 1747, and a machine that enabled a blind person to write letters to a sighted

person was made in 1808. Between 1829 and 1870 inventors in Europe and the

US patented numerous

writing machines with a wide range of designs. One of these early machines,

Charles Thurber's 1843-45 Patent Printer, is

pictured to the right and immediately below.

20th Century Painting of Hypothetical Office with Thurber's

1843-45 Patent Printer (MBHT)

20th Century Painting of Hypothetical Office with Thurber's

1843-45 Patent Printer (MBHT)

1852

Letter Typed on a Writing Machine for the Blind ~ Click on the box to the left to view an

enlarged scanned image of the first page of a letter written on a machine in 1852.

(If your browser automatically reduces the image so that it all fits on your

computer screen, click on the image on the screen. It should enlarge

again.) Each upper case

Roman letter is formed by a number of raised dots. Each dot has a minute

perforation through its center. The letter, which deals with a legal matter, was

written by Samuel Ellicott at his home, Brooke Meadow, located near Brookeville,

Maryland, north of Washington, DC, on April 14, 1852. This copy of the

letter was retained by Elliott while another copy was sent to his lawyer, J. J.

Stone. We have seen a similar letter by Elliott dated 1846. Although the identity of the

machine used to write this

letter is not yet known, the machine was designed for communication between blind people, or between a blind

and a sighted person. A number of typewriters for the blind were invented around

this time, e.g., the Fairbanks machine (1848) and the Beach machine (patented by

Alfred Ely Beach, one of the proprietors of Scientific American, in

1856). According to the Sandy

Spring Museum, "Totally blind since birth, Samuel Ellicott [1806-80] of

Brooke Meadow led a productive life: successful farmer and businessman,

incorporator and director of the Insurance Company. Several times a week

the dauntless Quaker [who, in the letter, addressed his lawyer as "Friend

J. J. Stone" and "thee"] walked the two miles to Brookeville to

fetch the mail." Brooke Meadow was built in 1823 and later was acquired by Samuel

and Sallie Duck Ellicott, who were living there in 1849 when gold was discovered on the

property. This was the first discovery of gold in Maryland.

"Miners dug a shaft 60 feet down, then an exploratory tunnel 30 feet

laterally, but found only a few thousand dollars worth of gold."

In

1852, John Jones received US

Patent No. 8,980 for the writing machine to the right, which he called a Mechanical

Typographer. (Photo of patent model courtesy of LIFE

Photo Archive)

In

1852, John Jones received US

Patent No. 8,980 for the writing machine to the right, which he called a Mechanical

Typographer. (Photo of patent model courtesy of LIFE

Photo Archive)

In

its 1862 catalog, the Eastman Business College advertised that students with

disabilities would be able to use Charles Thurber's Kaligraph

writing machine rather than writing with a pen. (Image to left from the 1862

college catalog is courtesy of Jim Drummond.)

In

its 1862 catalog, the Eastman Business College advertised that students with

disabilities would be able to use Charles Thurber's Kaligraph

writing machine rather than writing with a pen. (Image to left from the 1862

college catalog is courtesy of Jim Drummond.)

The the Rev. Rasmus Malling-Hansen (1835-90) of Denmark introduced the first of a number of models of his Writing Ball around 1869 (see image to left from the MBHT), and he received his first patent in 1870. Writing Balls won several awards during the 1870s on the European continent, where they were a commercial success, although the total number machines produced may have been only about 180. The machines were produced by hand. The International Rasmus Malling-Hansen Society website claims: "The writing ball was not only the first typewriter to be produced and sold in a relatively large quantity, it is also the fastest typewriter ever made, because of the unique construction of the 'ball'. Malling-Hansen was experimenting with the placement of the letters already in 1865 - and he succeeded in finding a placement of the letters that made the writing speed extremely fast. The model in the photograph to the right was introduced in 1878. The machine in this photograph was sold by Auction Team Köln. For photographs of a second 1878 model Writing Ball, click here.

The the Rev. Rasmus Malling-Hansen (1835-90) of Denmark introduced the first of a number of models of his Writing Ball around 1869 (see image to left from the MBHT), and he received his first patent in 1870. Writing Balls won several awards during the 1870s on the European continent, where they were a commercial success, although the total number machines produced may have been only about 180. The machines were produced by hand. The International Rasmus Malling-Hansen Society website claims: "The writing ball was not only the first typewriter to be produced and sold in a relatively large quantity, it is also the fastest typewriter ever made, because of the unique construction of the 'ball'. Malling-Hansen was experimenting with the placement of the letters already in 1865 - and he succeeded in finding a placement of the letters that made the writing speed extremely fast. The model in the photograph to the right was introduced in 1878. The machine in this photograph was sold by Auction Team Köln. For photographs of a second 1878 model Writing Ball, click here.

A larger model of the Writing Ball powered

by electricity was described in the January 15, 1876, issue of Harper's

Weekly. (See image to left) Production of Writing Balls ended when Malling-Hansen died in 1890. In 1909, Mares reported that

Writing Balls were still found in offices on the European

continent. (G. C. Mares, The History of the Typewriter, London,

1909, p. 230.) A number of original 1878 model Writing Balls survive, and this model has been reproduced.

A larger model of the Writing Ball powered

by electricity was described in the January 15, 1876, issue of Harper's

Weekly. (See image to left) Production of Writing Balls ended when Malling-Hansen died in 1890. In 1909, Mares reported that

Writing Balls were still found in offices on the European

continent. (G. C. Mares, The History of the Typewriter, London,

1909, p. 230.) A number of original 1878 model Writing Balls survive, and this model has been reproduced.

Typewriters in the Early Office

1870s The first typewriter that enabled operators to write significantly faster than a person could write by hand was the Sholes & Glidden Type Writer. Initially, models of this machine were marketed by E. Payson Porter. Porter used these machines at his National Telegraph College in Chicago, advertised them as early as 1868 (Peter Weil), and exhibited them in 1873 in Chicago (The Inter-state Exposition Souvenir, Van Arsdale & Massie, Chicago, 1873, p. 98). S.N.D. North, who subsequently became director of the U.S. Census, claimed that in 1872 he was the first person to put the typewriter into "actual practical business usage." He stated that on the Sholes & Glidden machine in question, the carriage was returned using a foot pedal, and the carriage returned "with a jar that made the machine tremble in every part. My machine did neither elegant nor uniform work, but after a week or two I was able to accomplish all my editorial writing upon it." (Quoted in The Phonographic Magazine, 1903, p. 259)

In 1874, E. Remington & Sons began to manufacture and market a subsequent

model of the Sholes & Glidden Type Writer at a price of $125. One of these machines is now worth on the order of $25,000 and owners need security cameras. Judging from serial numbers, about 5,000 Sholes &

Glidden machines were sold between 1874 and 1878. The machine evolved over those

years, with the result that several models can be

distinguished. Also, more than one version appear to have been produced at

the same time, e.g., a model in which the carriage was returned with a hand

lever and a model in which the carriage was returned with a foot treadle. According to a discussion published in 1891, "In the spring of

1876, [George W. N.] Yost , with three experts, went to Cincinnati...and

succeeded in selling over one hundred machines at retail before July 1. He

then employed Charles Wyman, from the assembling department at the factory, to

come to Cincinnati and keep the machines that had been sold in order and

continue the sales. In December...fewer than twenty-five per cent of the

machines were in use, the expert being unable to to keep them in working order,

and the instruments [i.e., typewriters] were continually being returned for

repairs." (Appletons' Annual Cyclopaedia...of the Year 1890,

1891. p. 810. The last Sholes & Glidden model was also sold as a

Remington No. 1. For a photograph of a Remington No. 1 being used in 1922, click

here

(Image DN-0075002, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago Historical

Society, Library of Congress).

Sholes & Glidden, Scientific American, Aug 10, 1872.

Sholes & Glidden, Scientific American, Aug 10, 1872.  Sholes & Glidden Typewriter, 1874, Smithsonian

Institution.

Sholes & Glidden Typewriter, 1874, Smithsonian

Institution.

Sholes & Glidden Typewriter, 1876 ad

Sholes & Glidden Typewriter, 1876 ad

Letter typed on Sholes & Glidden Typewriter, 1876.

The Sholes & Glidden machine typed only upper-case letters

Remington No. 1 Typewriter (Photo courtesy of LIFE

Photo Archive)

Remington No. 1 Typewriter (Photo courtesy of LIFE

Photo Archive)

1880s-1890s The first commercially successful antique typewriter, the Remington No.

2, was introduced in 1878. In his history of the U.S. Patent Office,

Robertson reports that around 1878 the Commissioner of the Patent Office

recognized that the Remington typewriter "would revolutionize the way

business was conducted and ordered its purchase and installation throughout his

offices. Other branches of the Interior Department followed suit." (Charles

J. Robertson, Temple of Invention, 2006, pp. 79-80) The first competing keyboard machine, the Caligraph, was

introduced in 1881. (Scientific American, Mar. 6, 1886) The next competing keyboard typewriters were the Crandall,

introduced around 1881, and the Hammond, introduced around 1884. Remington, Caligraph and Hammond were the three

major brands during the 1880s.

Remington No. 2 Typewriter, 1878

Remington No. 2 Typewriter, 1878

Typewriters did not become common in offices until after the mid-1880s. Typewriters are not even mentioned in G. L. Howe and O. M. Power, The Secrets of Success in Business, 1883, a 566 page volume on office practice and equipment written by teachers at business colleges. Yates reports that "The first use of the typewriter in the Illinois Central [Railroad] occurred in the New Orleans office in 1882 or 1883. It was not until 1886 that the first typed letters emerged from the Chicago and New York offices, and not until the 1890s that typed letters became more the norm than the exception in the company." (JoAnne Yates, Control through Communication, 1989, p. 131.) The workforce of the Scoville Manufacturing Co., which made brass products, increased from 314 in 1874 to 1,157 in 1892. Yates reports that "In 1888 the first typewritten letters appeared in Scovill's press books, interspersed with the still more common handwritten ones....By 1889 Scovill had hired a female typist." (p. 168) In 1886, the Du Pont black powder manufacturing company's Chicago agent obtained the company's first typewriter and hired a stenographer and typist. The main Du Pont office obtained its first typewriter in 1888. (p. 211)

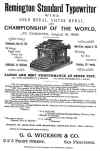

During 1874-79, when it was the only US producer of typewriters,

Remington's annual sales were roughly 1,000 machines. In a March 1882 ad for the Remington Perfected Type Writer, Remington claimed that 10,000 of its typewriters were in use. In the same ad Remington claimed thatits Perfected Type Writer "Writes three times as fast as best penman." According to advertising

claims made in 1891-92, Remington's annual sales increased to 5,000 typewriters during

1885 and 20,000 typewriters during 1890. Remington ads claimed that 40,000

Remington machines were in use in 1888. Remington sold somewhat over 100,000

typewriters between 1874 and 1891. The fantastic Remington advertisement to the right

is from 1885 (MBHT).

During 1874-79, when it was the only US producer of typewriters,

Remington's annual sales were roughly 1,000 machines. In a March 1882 ad for the Remington Perfected Type Writer, Remington claimed that 10,000 of its typewriters were in use. In the same ad Remington claimed thatits Perfected Type Writer "Writes three times as fast as best penman." According to advertising

claims made in 1891-92, Remington's annual sales increased to 5,000 typewriters during

1885 and 20,000 typewriters during 1890. Remington ads claimed that 40,000

Remington machines were in use in 1888. Remington sold somewhat over 100,000

typewriters between 1874 and 1891. The fantastic Remington advertisement to the right

is from 1885 (MBHT).

At $95-$100 each, the leading keyboard typewriters

were expensive, but they offered two clear advantages over handwriting, in

addition to legibility. First, typing on a keyboard machine was faster than writing with a

pen. In the mid-1880s, typists commonly used only the first two fingers

of each hand. Even in 1893, typists commonly used two, four, six, or eight

fingers, and at least some of the agents selling all the major keyboard

typewriter brands recommended using six fingers. (The Stenographer, 1893,

p. 319) The typewriter's advantage over the pen increased with the

adoption of touch typing, i.e., typing without looking at the keyboard. Touch

typing, which was consistent with use of six or more fingers, spread after a highly publicized contest in 1888

demonstrated its superiority (see

ad at right). Second,

typewriters could make multiple copies with the improved carbon paper that came

into use in the 1870s and with the typewriter stencils that were introduced in

the late 1880s. Carbon paper and stencil duplication are discussed in the

Museum's exhibit on copying machines.

While many typewriter designs were introduced during the 1880s and

1890s, the upstrike typewriter was the office standard

throughout this period. Upstrikes were blind-writers: they printed on the

underside of the platen, and operators therefore could not see their work while they were

typing. The illustration to the right shows how the hinged carriage of a Remington No.

2 was swung up so that the operator could check what she had typed. The most popular upstrike

typewriters were Remingtons, followed by Caligraphs in the 1880s and Smith Premiers in the 1890s. Caligraph claimed that

it sold 10,000 machines between 1881 and 1886, 10,000 more in 1887, and another 10,000 in 1888.

While many typewriter designs were introduced during the 1880s and

1890s, the upstrike typewriter was the office standard

throughout this period. Upstrikes were blind-writers: they printed on the

underside of the platen, and operators therefore could not see their work while they were

typing. The illustration to the right shows how the hinged carriage of a Remington No.

2 was swung up so that the operator could check what she had typed. The most popular upstrike

typewriters were Remingtons, followed by Caligraphs in the 1880s and Smith Premiers in the 1890s. Caligraph claimed that

it sold 10,000 machines between 1881 and 1886, 10,000 more in 1887, and another 10,000 in 1888.

According to an 1887 trade press account, "The universal popularity of writing machines is one of the features of the present day. Figures furnished by the various makers show that between 60,000 and 70,000 are already in use. Of this number the Remington people claim to have about 35,000; Caligraph, about 15,000; while the balance is made up of the Hammond, Crandall, Hall, Columbia, Sun, World, and others. About one-sixth of the total produce finds a sale in New York city." (The Office, Sept. 1887, p. 182; this same issue also contains an advertisement in which Hammond claimed that 4,000 of its machines were in use.)

Smith Premier claimed that it sold

27,000 typewriters between 1889 and 1892, 100,000 typewriters between 1889 and 1899, and 300,000

typewriters between 1889 and 1907. In 1892, Remington claimed to be producing

more typewriters than all other "high priced" brands combined. In 1895, Remington

reported that a survey of the 34 leading office buildings in New York City

showed that Remington machines accounted for 78% of 3,426 writing machines in

operation. In a similar survey of 37 buildings in Chicago, Remingtons accounted

for 73% of 3,523 writing machines. In 1896, in 16 buildings in

Philadelphia, Remingtons accounted for 79% of 1,267 writing machines. In 1904, Remington claimed that

its machines accounted for 55% of the 33,661 typewriters used for instructional

purposes in schools in the US and Canada.

In addition to

upstrikes, single-element Hammond typewriters were used in some late 19th century offices.

In 1889, the Elmira School of Commerce advertised openings for 150 students to

learn to operate Hammonds. (See ad at right.) An 1890 Hammond advertisement claimed that the

US Government

had purchased seventy-five of the company's typewriters in a single order. The photograph to

the left shows a 1905 Hammond No. 12.

In addition to

upstrikes, single-element Hammond typewriters were used in some late 19th century offices.

In 1889, the Elmira School of Commerce advertised openings for 150 students to

learn to operate Hammonds. (See ad at right.) An 1890 Hammond advertisement claimed that the

US Government

had purchased seventy-five of the company's typewriters in a single order. The photograph to

the left shows a 1905 Hammond No. 12.

A

typewriter desk with a Sholes and Glidden typewriter, shown in the illustration

to the left, appears in the 1876 advertisement for Densmore, Yost & Co.

A typewriter desk that was supplied with Remington typewriters around 1880 is

pictured to the right (MBHT)

A

typewriter desk with a Sholes and Glidden typewriter, shown in the illustration

to the left, appears in the 1876 advertisement for Densmore, Yost & Co.

A typewriter desk that was supplied with Remington typewriters around 1880 is

pictured to the right (MBHT)

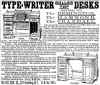

Typewriter

desks, arranged for Remington, Hammond, and Crandall typewriters, were advertised

in 1888, the date of the advertisement to the left.

Typewriter

desks, arranged for Remington, Hammond, and Crandall typewriters, were advertised

in 1888, the date of the advertisement to the left.

In 1893, the producers of the five leading upstrike typewriter brand--Remington,

Caligraph, Smith Premier, Densmore and Yost--merged to form the

Union Typewriter Company of America, or Typewriter Trust, as it was referred to

in newspapers of the era.

The 1890 Catalogue of the Albany Business College, Albany, NY, contains illustrations of two upstrike typewriters (Remington, Caligraph) and the Hammond, and states that the college had 20 machines of these three brands. The catalog also states that over 200 typewriters were in use for instructional purposes at business colleges and shorthand schools in New York City. In 1895, the New York Business College used Smith Premier, Remington, Hammond and Caligraph machines, as well as a New York City house cleaning service. (The Stenographer, July 1895, p. 6) An 1896 textbook, O. R. Palmer, Type-Writing and Business Correspondence, Philadelphia, includes illustrations and instructions for three upstrike typewriters (Remington, Caligraph and Smith Premier) and for the Hammond. The 1897 Catalogue and Prospectus of Eastman Business College, Poughkeepsie, NY, contains drawings of three upstrike machines (Remington No. 2, Caligraph and Smith Premier). Classroom photos in the same catalog also show mainly upstrikes but also a few Hammonds. And the catalog contains letters from the makers of Remington, Caligraph, Smith Premier, and Hammond machines asking the college to send them students trained to operate their machines so that they can place them with employers. An 1899 textbook, E. Collyns, The Typist's Manual, London, features two upstrikes (Remington, Yost). The newest models of all these machines, as well as Densmore upstrikes, were $95 or $100.

The image to the right shows an ad

for typewriter ribbons patented in 1890-92) In 1903, a Remington ad

claimed that "More than 10,000 Remington Typewriters are used for

instruction purposes in the schools of the United States and Canada--over 2,200

more than all other makes of writing machines combined." (The

Book-Keeper, June 1903, p. 81)

The image to the right shows an ad

for typewriter ribbons patented in 1890-92) In 1903, a Remington ad

claimed that "More than 10,000 Remington Typewriters are used for

instruction purposes in the schools of the United States and Canada--over 2,200

more than all other makes of writing machines combined." (The

Book-Keeper, June 1903, p. 81)

Most discussions of early typewriters focus on the principal mechanical and

visible distinctions among the various models. However, as typewriters

evolved there were numerous other  changes that are not immediately obvious.

There were improvements in basic design elements, such as the system of linkages

from the key to the type, and features that maintained type alignment. These

improvements increased typing speed and quality. Some new designs required

substantially fewer parts than earlier machines. As a result, the labor cost for

assembly was lower. Also, many features that made typing easier and faster were

added, such as automatic line-spacing (return of the carriage started a new

line), automatic ribbon reversal, margin locks and releases, and tabulator

mechanisms. Machines also became more reliable and quieter.

changes that are not immediately obvious.

There were improvements in basic design elements, such as the system of linkages

from the key to the type, and features that maintained type alignment. These

improvements increased typing speed and quality. Some new designs required

substantially fewer parts than earlier machines. As a result, the labor cost for

assembly was lower. Also, many features that made typing easier and faster were

added, such as automatic line-spacing (return of the carriage started a new

line), automatic ribbon reversal, margin locks and releases, and tabulator

mechanisms. Machines also became more reliable and quieter.

1900s During the first decade of the 20th century, the

standard for the office typewriter

changed from the upstrike to the front strike

typewriter, a visible

writing machine: the typist could see what she had typed because the machine printed on the front of the platen. The most

popular front strike was the Underwood No. 5, which won many speed typing

contests. In 1900, an advertisement for the Underwood typewriter stated that the

US Navy Department had purchased 250. Underwood sold nearly four million of its No. 5 and its similar No. 3

and No. 4 typewriters between 1901 and 1931. Another front strike

typewriter brand that is often recognizable (because of its distinctive shape) in early 20th century photographs of small offices

is the flatbed Royal, which was introduced in 1906.

1900s During the first decade of the 20th century, the

standard for the office typewriter

changed from the upstrike to the front strike

typewriter, a visible

writing machine: the typist could see what she had typed because the machine printed on the front of the platen. The most

popular front strike was the Underwood No. 5, which won many speed typing

contests. In 1900, an advertisement for the Underwood typewriter stated that the

US Navy Department had purchased 250. Underwood sold nearly four million of its No. 5 and its similar No. 3

and No. 4 typewriters between 1901 and 1931. Another front strike

typewriter brand that is often recognizable (because of its distinctive shape) in early 20th century photographs of small offices

is the flatbed Royal, which was introduced in 1906.

E. H. Beach, Tools of Business, 1905, p. 182, reported an estimate that

200,000 typewriters were produced in the U.S. annually, of which at least half

were exported, mainly to Europe. Beach also reported claims that German

imports of U.S. typewriters exceeded German production.

A key year in the switchover from upstrike to front strike machines was 1908, when Remington and Smith Premier, until then leading sellers of upstrike machines, introduced front strike models. National advertising for new upstrike typewriters terminated abruptly by the end of 1908, sales dropped sharply, and production ceased around 1914. Based on serial numbers reported in The American Digest of Business Machines, 1924, p. 608, evidently Remington produced 33,000 upstrike machines during the six years from 1908 to 1914. That is fewer upstrike machines than Remington produced in any single year during the preceding decade. Smith Premier also continued to produce its No. 2 through No. 9 models, all of which were upstrikes, until 1914. (ETCetera, No. 28, Sept. 1994)

A unique

typewriter that was popular in offices during the 1900s and

1910s was the Oliver Visible Typewriter, a downstrike model. Over one million Olivers were sold during the 32 years (1893-1926) they were

produced in the US. The photo to the left shows a 1914 Oliver No. 7.

A unique

typewriter that was popular in offices during the 1900s and

1910s was the Oliver Visible Typewriter, a downstrike model. Over one million Olivers were sold during the 32 years (1893-1926) they were

produced in the US. The photo to the left shows a 1914 Oliver No. 7.

1920s-1930s In contrast to the several scores of companies that produced typewriters in earlier decades, by the 1920s the US typewriter industry had substantially consolidated. During the 1920s and 1930s, the big four front strike typewriter companies--Underwood, Royal, Remington and Smith-Corona--accounted for 80% of the dollar value of typewriters sold in the US. Engler reports that Underwood had a 50% market share in 1920 but later lost ground so that each of the big four had a market share of about 20% immediately prior to World War II. (George N. Engler, The Typewriter Industry, Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, 1969.) Yet, a number of small typewriter manufacturers, with a combined share of about 20%, existed during this period.

Electric front strike typewriters were introduced in

the 1920s and 1930s, but they did not become a major factor in offices until

after World War II.

Peter O. Hegrum, Madison, with three typewriters he

made, 1931. (Minnesota Historical Society, Neg. No. 26103)

Peter O. Hegrum, Madison, with three typewriters he

made, 1931. (Minnesota Historical Society, Neg. No. 26103)

1960s

Manual and electric front strike typewriters

remained

the office standard until the IBM Selectric

with its golf-ball type-element was introduced in 1961. The Selectric's carriage

was stationary while the type-element moved back and forth across the page. As

was true of earlier single-element typewriters, the type-element on the

Selectric could be changed to permit writing in different fonts and

languages.

1960s

Manual and electric front strike typewriters

remained

the office standard until the IBM Selectric

with its golf-ball type-element was introduced in 1961. The Selectric's carriage

was stationary while the type-element moved back and forth across the page. As

was true of earlier single-element typewriters, the type-element on the

Selectric could be changed to permit writing in different fonts and

languages.

Early Office Typewriters With the exception of the Hammond, all the "office" typewriters mentioned above were large, heavy and sturdy. All were keyboard machines. And, with the exception of the Hammond and IBM Selectric, all used type-bars. A type-bar is a rod with attached type that prints a letter when a key is pressed. One reason that keyboard machines with type-bars were dominant in offices from the 1880s through the 1950s is that these typewriters were faster than single-element keyboard typewriters or index typewriters. For photographs of early office typewriters and additional information about them, click here.

Other Early Typewriters In

addition to the kinds of typewriters that were the office standards, many other

type-bar and single-element keyboard machines, as well as index typewriters that

did not have keyboards, were

sold during

the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many of these other typewriters were

smaller, lighter, slower and cheaper. These other typewriters do not appear to have

played a significant role in early offices, although some of the sales of all of

them were presumably accounted for by offices, and Bar-Locks appear to have been

popular in offices in the UK. In any event, they rarely appear in

early photographs of offices or typing classes.

Notes:

The acornym MBHT indicates that an image is used courtesy of the Museum

of Business History and Technology.

We thank Ron North and Larry Wilhelm for permission to use several of their

photographs of typewriters.

Antique Typewriter Books

Michael Adler, Antique Typewriters: From Creed to Qwerty, Schiffer, 1997.

Darryl Rehr, Antique Typewriters & Office Collectibles, Collector Books, 1997.

Thomas A. Russo, Mechanical Typewriters, Schiffer, 2002.

The Classic Typewriter Page (Richard Polt)

Machines of Loving Grace (Alan Seaver)

Typewriters by Will Davis

Portable Typewriters (Richard Milton)

The Virtual Typewriter Museum (Paul Robert)

The Chestnut Ridge Typewriter Museum (Herman Price)

Typewriter.be (Wim Van Rompuy)

Typewriters.ch (Georg Sommeregger)

Antique Typewriters (Martin Howard)

Typewriters (Arnold Betzwieser)

Early Office Museum

Typewritercollector.com (Anthony Casillo)

The Antikey Chop Typewriter Collection (Greg Fudacz)

Australian Typewriter Museum (Bob Messenger)

Chuck & Rich's Antique Typewriter Website and Museum (Chuck Dilts & Rich Cincotta)

Collectors Weekly: Antique Typewriters

Yahoo! Groups: Typewriters (You must sign up to access)